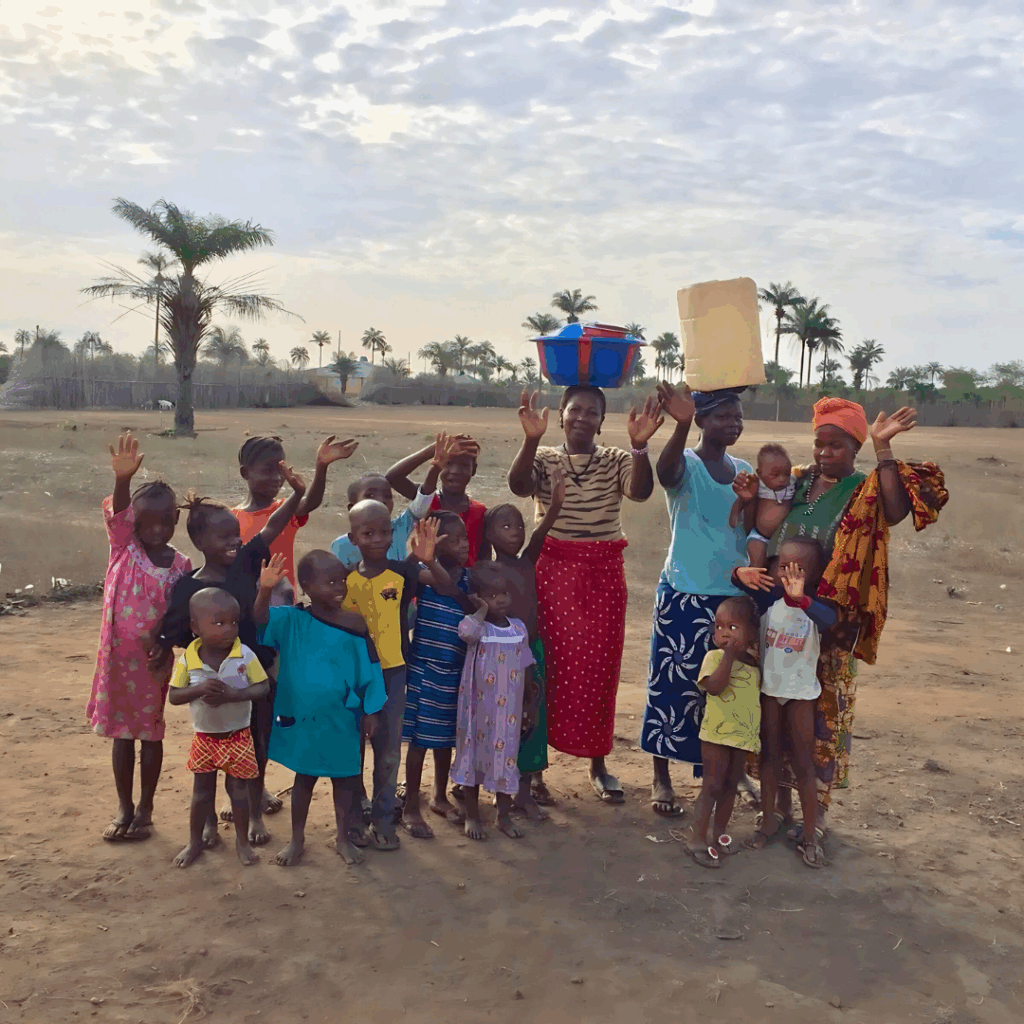

The Kono Tribe in Sierra Leone follows a unique naming tradition for their children. A mother’s first son is named Sahr. Her second son is named Tamba. Her third son is named Aiah, etc. etc. The daughters follow a similar naming convention with Sia being the first daughter followed by Kumba, Finda, etc. If you spend time in Kono District, the home of the Kono tribe, you find the people very friendly and welcoming. It doesn’t take long for someone to offer you a local name. That’s how I inherited and adopted the name Tamba (I am my mother’s second son), and to this day there are people in Sierra Leone that call me this name even years later when I return to visit.

Ten years ago, when Jericho Road, under Phebian Abdulai’s leadership, took the steps to open our first global clinic site, Sierra Leone was facing a really challenging time. The country was facing an Ebola outbreak, and it was causing deaths and tragedy even in Kono District. However, part of the often-untold tragedy of the outbreak was how it affected access to primary healthcare even apart from Ebola. Patients were often afraid to seek treatment at a health facility because of well-founded fears of catching Ebola while being treated for something else. Health providers were also sometimes afraid to care for patients, particularly patients with fevers prior to the disease being ruled out.

At the new clinic facility, we tried to walk that line carefully to provide the best treatment we could offer to anyone who came for help. On the other hand, we also tried to be thoughtful and provide safety for our team members. Each patient and family member entering the clinic property had their temperature checked. Patients who had fevers or other symptoms concerning for a possible Ebola infection were cared for in a temporary holding area separate from the rest of the facility. This helped mitigate the risk of cross infection. Caregivers going into this holding treatment area were required to wear a lot of personal protective equipment and followed strict safety procedures while caring for patients.

Soon after we opened the clinic a mother presented with her very sick febrile infant son. We rushed the mother and son into the holding area. I personally ran down to the pharmacy requesting that the team start mixing up antibiotics and antimalarial medications. I then entered the PPE donning room and started dressing out in Personal Protective Equipment to enter the holding area. As I finished putting on the protective gear the pharmacy team handed me the newly mixed medicines.

Sadly, though I had barely taken two steps with the medicines in my hands when I heard incredible wailing. I ran into the holding area and saw the now lifeless body of her infant son. My training at that point kicked in. I dropped to my knees and started pumping the tiny infant’s chest with my two fingers. However, within a short amount of time I realized that the efforts were medically futile. Even if a miracle happened and we successfully resuscitated this baby, there was literally not a single health facility within the entire country able to provide the critical care level of support the child would need post resuscitation. With tears gathering at the corner of my eyes, I made the painful decision to stop the chest compressions. With Ebola in the community, we had to report the death to the district authorities, and they sent out a burial team to pick up the child and test him for Ebola. Thankfully, for his family’s sake his test later returned negative. Although we’ll never know for sure what led to the child’s death, the most likely culprits based on his symptoms were either malaria or pneumonia. If the child had presented even hours or a half a day earlier, there’s a pretty good chance that the medications the pharmacy team mixed up for me would have had time to do their work.

In conversation with the parents afterwards I learned that it wasn’t that they weren’t worried or that they didn’t care. They had tried making the best decisions they could with the resources they had. Afraid to take their child to most clinics because of Ebola, they had traveled many miles on a motorcycle taking the child to a series of pharmacies trying to find help. With their money exhausted, they had decided to come visit this new clinic that had just opened. Unfortunately, by the time they arrived it was too late.

Crying, the mother told me that her baby’s name was Tamba. The same name I had recently adopted for myself. Still crying, she told me about Sahr, her firstborn son. He had also died of a preventable illness prior to his first birthday. I was deeply affected by that experience and resolved again that day that I wanted to do my part in creating a world in which fewer mothers experience the tragedy of a single child’s premature death, let alone the premature death of multiple children.

In my faith tradition we hold to a belief that one day our Creator will make all things right with a new heaven and a new earth (where death and suffering can no longer occur), but in the meantime, we each have a role to play in working towards the peace and wholeness of our neighbors. This includes even our global neighbors living in places like the remote corners of Sierra Leone, Congo, and Nepal.

A reflection by Karlin Bacher, MA, BSN, RN, Director of Population Health at Jericho Road.